"Accident" in the firing of Jianzhan bowls

Many ceramic products have an extraordinary beauty, and in a sense this beauty is natural, it occurs naturally. It is impossible to reproduce it intentionally, and even the master who creates the product cannot predict what it will be like.

Retelling from the words of: Lü Chenglong (Chinese: 吕成龙, pinyin Lǚ Chénglóng)

(Full-time researcher at the Forbidden City Museum in Beijing, deputy head of the section of tableware and utensils, board member of the Scientific Society for the Study of Ancient Chinese Ceramics and Porcelain)

Compiled by: Xuan Wu (Chinese: 宣武, pinyin Xuān Wǔ)

Such beauty can be called a creation of nature, in other words, a kind of “chance” or, as the Chinese say, a “chance meeting” (Chinese: 邂逅, pinyin: Xièhòu, plang.: Sehou). This is especially characteristic of tea bowls in the Fujian Jianyao (Chinese: 建窑, pinyin: Jiànyáo) firing technique, created during the Song Dynasty and colloquially called “Jianzhan” (Chinese: 建盏, pinyin: Jiànzhǎn). The term “Jianzhao” literally means “Ware from the pottery kilns of the Jianyang region” (a region in Fujian province), and the second term “Jianzhan” means “Tea bowls from the Jianyang region”.

Jianzhan bowls differ from other types of porcelain in that their artistic style is characterized by a desire for simplicity and artlessness, and is devoid of any pretentiousness or unnatural elegance. It can even be said that the inner desire of the Jianzhan style - the desire to be a creation of nature - in a sense reached its limit in this firing technique, and the emergence of this unique style is closely connected with the aesthetic views of the Chinese in that era. Representatives of the intelligentsia (from the service class) of the Song era adhered to the position of naturalness in aesthetics, placing the beauty of nature above all else. They emphasized the importance of returning to the original sources of the universe, the original harmony of nature, and in art they valued simple charm and natural beauty. They developed this approach to the level of an independent philosophy, the ultimate goal of which was insight and knowledge of the true nature of things.

It was during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) that the Jianzhan style of bowls was created, a style that was reduced to extreme simplicity in shape, glaze pattern, and other aspects. Its peculiarity lies in unexpected effects (such as color and pattern) that accidentally arise during the firing of bowls, but at the same time these effects are very beautiful and cause aesthetic pleasure in people.

In general, there are three varieties of Jianzhan tea bowls: Yaobian (Chinese: 曜变, pinyin: Yàobiàn), Zheguban (Chinese: 鹧鸪斑, pinyin: Zhègūbān), and Tuhao (Chinese: 兔毫, pinyin: Tùháo). The most valuable and worthy of mention is, of course, the Yaobian variety, which literally means “shimmering” or “sparkling.” These bowls express the beauty of the Jianzhan style to its fullest extent. Their appearance is the result of chance in the firing process, or, as they say in Chinese, “chance encounter” —an effect that can be “encountered,” but cannot be created intentionally. Three Yaobian bowls from the Song Dynasty, called the Yaobian Tianmu (Chinese: 曜变天目, pinyin: Yàobiàn Tiānmù, in Japanese: "Yōhen Tenmoku", literally "Yaobian from Mount Tianmu"), have been passed down intact from generation to generation and are now kept in Japan. One of these bowls is called the "First (i.e. best) bowl in the world" (Chinese: 世界第一盏, pinyin: Shìjiè dìyī zhǎn), it is kept in the Seikado Bunko Museum in Tokyo. It is also called the "Bowl of Rice Ears", and the Japanese call it the "Universe in a Bowl".

The spots or specks that are characteristic of Yaobian cups make some people feel as if they are “dipping into the glaze”. What most fascinates people who have seen Yaobian Tianmu cups is the iridescent seven-colored glow that each speck emits under the influence of light, and what is most striking is that this glow constantly changes, as if following the gaze of the observer. I was fortunate to have seen this “universe in a cup” in person once, and I can confirm that there really is a universe in this cup – no matter how much I looked at this cup, I could not look enough. It is amazing how such a small cup can have so many shades and colors, so that it is really difficult for the observer to take his eyes off it.

As mentioned, the appearance of Yaobian and Zheguban bowls is the result of an "accident" that occurred during the firing process, that is, at some stage of firing or in some technical process, something unexpected happened, and it is difficult for us to understand what exactly, but the final result really looks like a real gift from above. It did not depend on the will of people, so they say that this shining effect can only be "accidentally encountered", it is impossible to achieve it intentionally.

Samples of Jianzhan bowls were provided to us by:

One of the famous generations of tableware that was popularized by tea culture is Heiyuqi (Chinese: 黑釉瓷, pinyin: Hēiyòucí), which literally means "black-glazed porcelain". The firing of this style of tableware began in the late Tang Dynasty (875–907), and it flourished during the Northern Song (960–1127) and Southern Song (1128–1279) periods, declined during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), and continued into the Qing Dynasty before ceasing. In 1979, the Central Academy of Fine Arts (now Tsinghua University), the Fujian Provincial Light Industry Research Institute, and the Jianyang District Porcelain Factory formed a small research team to restore and study in detail the firing technology of Jianzhan bowls of the Song Dynasty.

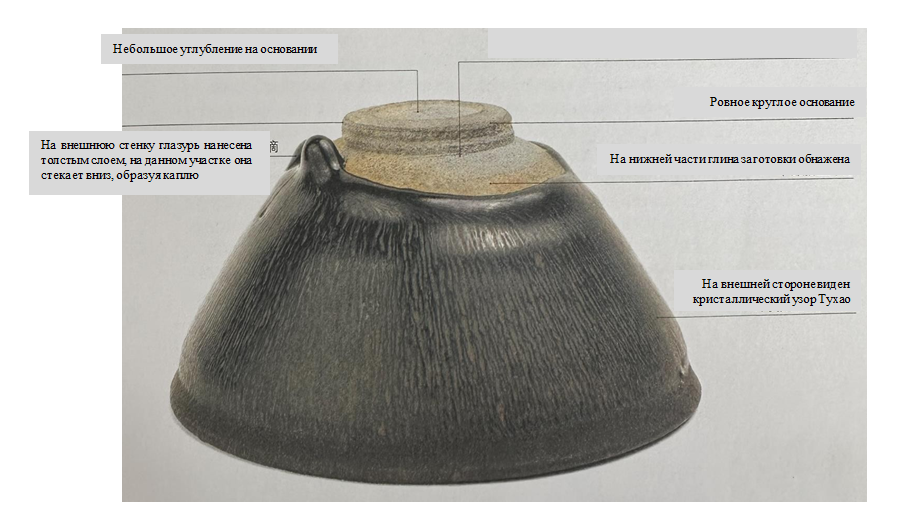

Traditionally, Jianzhan style bowls were mainly produced in Shuiji (Chinese: 水吉镇, pinyin: Shuǐjí Zhèn) township in Jianyang (Chinese: 建阳, pinyin: Jiànyáng) district of Fujian province, using iron-rich clay and ore glaze mined in the same region. As a result of firing in a kiln at a high temperature (approximately 1300 °C), changes occurred in the porcelain that could produce such diverse color effects on the glaze as Tuhao (Chinese: 兔毫, pinyin: Tùháo), Yudi (Chinese: 油滴, pinyin: Yóudī) or Zheguban (Chinese: 鹧鸪斑, pinyin: Zhègūbān), Wujin (Chinese: 乌金, pinyin: Wūjīn), Chaemo (Chinese: 茶叶末, pinyin: Cháyèmò), Shihong (Chinese: 柿红, pinyin: Shìhóng) and others.

Currently, there is much debate in academic circles about the exact definition of the term "Jianzhan" . According to the narrowest definition, the term "Jianzhan" can only be used to describe bowls made in the original place of production, that is, in Shuiji Township, using the reduction firing method and using local clay and ore glaze. Other researchers adhere to the "Vast Jianyao" theory , according to which the place of production of Jianzhan bowls can be considered not only Shuiji Township itself, but a larger region, including the ancient pottery settlements of Yulinting (Chinese: 遇林亭, pinyin Yùlíntíng) in the Wuyi Mountains, as well as the settlement of Chayang (Chinese: 茶阳窑, pinyin Cháyáng Yáo) in the city of Nanping County. Finally, some researchers use the term Jianzhan to refer to all Heiyuqi -style ware made using the Jianyao technology.

For example, according to the most popular theory of today, that of the authoritative ceramic master Li Da (Chinese: 李达, pinyin: Lǐ Dá), any bowl that has been fired to achieve the “oil drop” effect using the “duckweed technology” (Chinese: 浮萍机理, pinyin: Fúpíng Jīlǐ, see below for more details) can be called a Jianzhan bowl, and this is the most important and, according to this theory, the only characteristic of Jianzhan bowls. This theory has become especially widespread in Taiwan and Japan.

Color and pattern

Depending on the color of the glaze, Jianyao porcelain ware is divided into two large groups: ware with black glaze and ware with glaze of other colors . Black glaze is the result of iron crystallization and is usually applied in a fairly thick layer. During firing of the ware in a kiln at a high temperature (1300 °C), a chemical process of reduction of simple iron, which is part of the glaze and clay, occurs, and it is this process that leads to the formation of various patterns on the dishes depending on changes in the temperature in the kiln and environmental conditions. The process of pattern formation is difficult to predict and control, in Chinese it is called "Yaobiang" (Chinese: 窑变, pinyin Yáobiàn, literally "transformation in the kiln"; not to be confused with the name of the variety of Jianzhan bowls - Yaobian (Chinese: 曜变, pinyin Yàobiàn).The firing temperature of the products depends on the desired pattern and color of the glaze. If we arrange the glaze types in order of increasing firing temperature, we get the following sequence: Chaemo, Wujin, Yudi, Tuhao, Jiangyou, Shihong. The firing temperature for Tuhao glaze is 1330 °C (±20 °C), for Yudi glaze - 1280 °C (±20 °C), for Jiangyou - 1350 °C (±20 °C).

Tuhao glaze ware is the most characteristic and typical representative of Jianyao ware, and it was produced in the largest quantity (for example, Yudi glaze ware is much less). In addition, in terms of both market value and aesthetic value, such types of multi-colored glazes as Guilewen, Huipi, Huibai, Jianyou , etc. are still second-rate products, the appearance of their glaze is the result of too low or too high firing temperature. As for the Yaobian (Chinese: 曜变, pinyin: Yàobiàn, "shimmering") effect, it is an extremely rare phenomenon, an unlikely accident, which is almost impossible to achieve intentionally.

Glaze from raw ore

The ore for the glaze of traditional Jianzhan bowls was mined in the mountain valleys of the Jianyang area, which are called "glaze depositories" in Chinese. The characteristics of this type of glaze are a very high content of iron and phosphorus, as well as high acidity and viscosity, due to which the glaze is easy to apply in a thick layer and has a deep color palette. Plant ash was also mixed with the mined ore glaze to increase the calcium content. In China, in modern ceramic research, this glaze is called "iron crystal glaze".

Although traditional Jianzhan bowls, as the Chinese say, "enter the kiln with one color and come out with ten thousand colors," the same type of glaze was used in their production, with different potters varying the ratio of components in its composition to some extent. The variety of patterns and colors of the glaze is simply a consequence of different temperatures in the kiln, as well as different environmental conditions during the firing of a particular bowl. When Jianzhan bowls are fired in our time, two different patterns are obtained - Tuhao and Yudi - use glazes of different compositions.

It is equally important to note that nowadays you can also find Jianchazhen bowls on the market that are made using either chemical glazes or chemical additives (such as fluxes) mixed into the natural glaze to achieve the desired colors and patterns even at insufficiently high temperatures. At the moment, there is no scientific evidence that such tableware meets food safety standards. In addition, no government quality control agency has yet tested or issued any safety certificates for such products, so you should be careful when purchasing such products for use as tableware.

Pictured: Yaobian Tianmu bowl, now housed in the Seikado Bunko Museum in Tokyo.

- Comments

- Vkontakte