Varieties of Jianzhan bowls

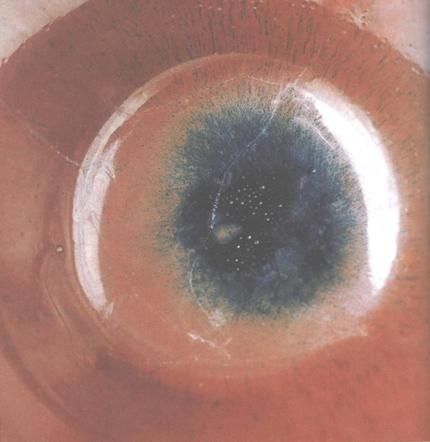

Yaobian bowls are a rare treasure that cannot be created, but can only be “met” by chance, which is why master potters sometimes had to search for this “meeting” their entire lives.

Some believe that the word "Yao Bian" (Chinese: 曜变, pinyin: Yàobiàn) is of Japanese origin, however, researcher Ma Weidu 1 notes in one of his articles that it is originally Chinese, but over time it fell out of use, and instead of it, the terms "Haobian" (literally "Shimmering like wool"), "Yibian" ("Changing") and "Yao Bian" ("Transforming after firing in the kiln") began to be used to denote such bowls, which are believed in scientific circles to mean the same thing. Some authors used to have a superstitious opinion that before firing the bowls in the kiln, a ritual of sacrificing the blood of a virgin was performed, which was dripped onto the bowls, after which the blood solidified on the surface, creating a Yaobian pattern.

All three authentic Yaobian bowls, passed down through generations—the so-called “Three Peerless Yaobian Bowls” (Chinese: 曜变三绝碗, pinyin: Yàobiàn Sānjuéwǎn)—are now in Japan, one in the Seikado Bunko Museum in Tokyo, another in the Ryokoin Hall of the Daitoku-ji Buddhist Temple in Kyoto, and the third in the Fujita Art Museum in Osaka.

The Yaobian effect itself is a multitude of irregularly shaped circles on a black background, the circles themselves are yellow, and a dazzling glow emanates from their edges, reminiscent of a rainbow, in which blue predominates, hence the effect got its name. The shining circles are located mainly on the inner walls of the bowls and shimmer when you move your gaze. It is the presence of such shining circles that is the criterion for determining Yaobian. How are they formed? During firing, at the moment when a pattern in the form of "oil drops" (Yudi) appears on the black glaze, trivalent iron (which is contained in Fe 2 O 3 ) quickly turns into divalent (contained in FeO), which is a strong solvent. Before simple iron is restored from FeO, it can very quickly "melt" into the glaze, due to which the pattern in the form of circles disappears. However, before the circles disappear, a very thin film may form around the edges, which, under the light, gives the effect of iridescent colors. If the glaze in this state has time to harden in time, then there is a chance to get a Yaobian bowl, otherwise the pattern completely disappears and you just get a bowl with black glaze. The probability that hardening in the kiln will happen at the right moment tends to zero, this is one of the reasons why Yaobian bowls have become a national treasure.

Note 1. Ma Weidu (Chinese: 马未都, pinyin: Mǎ Wèidū) is a Chinese collector, cultural scholar, writer, and the founder and director of the Guanfu Museum.

Tuhao

There are two theories about the origin of the name "Tu Hao" (Chinese: 兔毫, pinyin: Tùháo), which literally means "Hare's Hair" . According to the first theory, the pattern is called so because it resembles the hair of a hare, while the second theory says that the pattern is compared to a writing brush made of hare's hair. In any case, the criterion for defining Tu Hao was given by Hui Zong , one of the emperors of the Song era, in his "Treatise on Tea" (Chinese: 大观茶论, pinyin: Dàguān Chá Lùn): "The color of good bowls is blue-black, and the sparkling threads on them are long." In other words, the "hare's hairs" should seem to "hang" from the edges to the base of the bowl, filling all the space on the walls. In addition, depending on the color of the glaze, Tuhao bowls are divided into such varieties as "Brown Tuhao", "Golden Tuhao", "Silver Tuhao" and "Blue Tuhao" . During the firing process at a high temperature, as a result of burning pine wood, a large amount of carbon monoxide ( CO , carbon monoxide) is formed, which acts as a reducing agent during firing - it enters into a complex oxidation-reduction reaction with iron (III) oxide ( Fe 2 O 3 ) contained in the glaze ( 3CO + Fe 2 O 3 ═ 2Fe + 3CO 2 ). As a result, simple iron is released, which then gets inside the glaze on bubbles that appear on the surface of the glaze as a result of its boiling. Then the iron, following the melted glaze, flows down the walls of the bowl, forming a characteristic thread-like pattern.

As the glaze runs down the sides of the bowl, it can form areas of uneven thickness. The "hare hairs" are concentrated at the edges of the bowl, gradually becoming rarer and less noticeable towards the bottom. Therefore, they are said to resemble seaweed, which is clearly visible on the surface of the water, but difficult to distinguish in the depths.

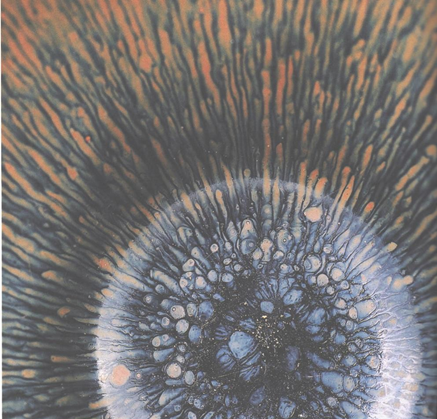

In the photo: Part of the Tuhao bowl (Song era).

During the above transformation, iron oxide (FeO) may be formed for a short time , which may result in silver or blue Tuhao . This is due to the ratio of divalent iron (contained in FeO ) to trivalent iron (contained in Fe2O3 ) during the reduction firing, and this necessary ratio is maintained for an extremely short time. If the content of trivalent iron is even slightly higher than required, the silver Tuhao will immediately turn gray, the pattern will look dirty, and the probability of obtaining blue Tuhao is even lower.

Therefore, regardless of whether you choose a new Jianzhan bowl or an ancient one, the sign of a high-quality Tuhao is thin, long, clear "hairs", densely and evenly distributed along the inner and outer walls of the bowl from the edges to the base. In the case of high-quality silver Tuhao, the "hairs" should be snow-white and shiny, and gold and blue Tuhao should give a gold and blue shine, respectively. In addition, it is worth paying attention to the fact that the glaze on the edges of the bowl is applied in a thinner layer.

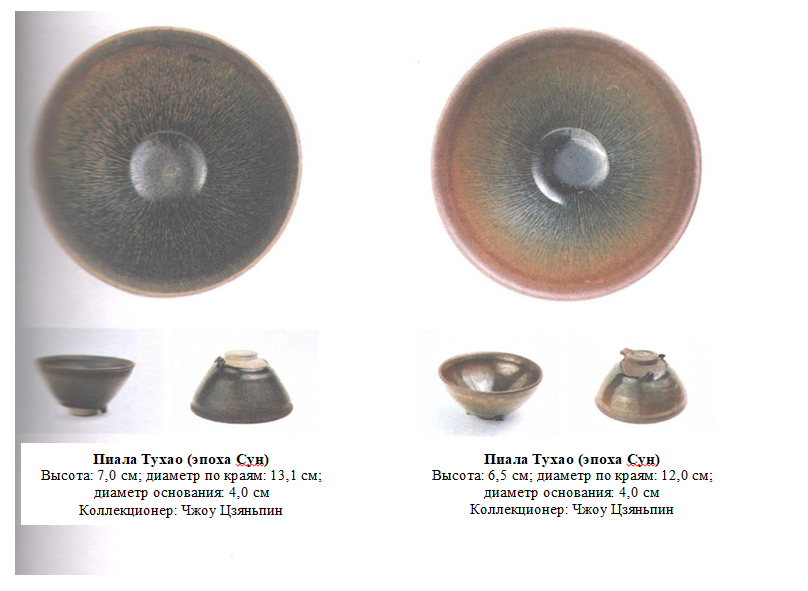

Both bowls in the photo have thin and long "hare hairs", but on the left bowl they are evenly distributed over the entire surface - bowls of this level of craftsmanship are usually kept in museums. On the right bowl, the "hairs" are thinner, longer and straighter, the effect of "shine of pearls in a shell" is already noticeable on the surface of the glaze, and the "hairs" near the edges have already disappeared.

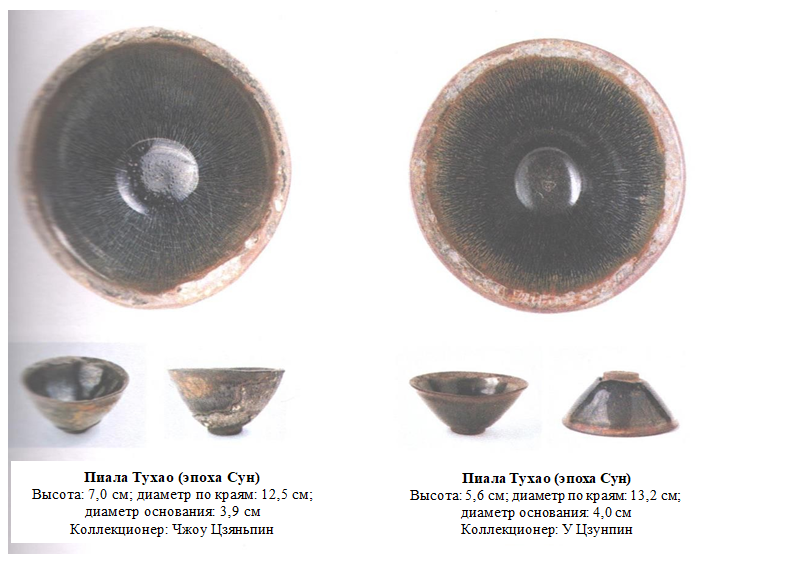

The left bowl in the photo is an example of Silver Tuhao, and the right one is Blue Tuhao. The edges and the outside of the left bowl were glued to the crucible during the firing process, while the right bowl had a defect on the edges due to the presence of silver in its composition.

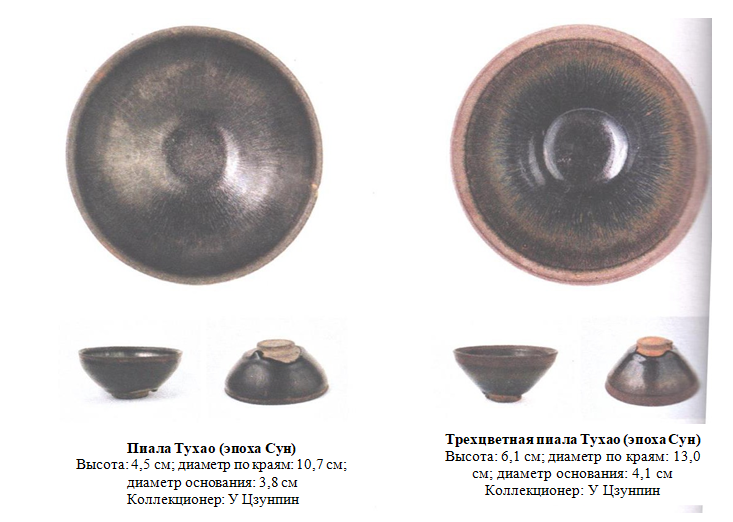

The left bowl in the photo is shaped like a "Liankou", which makes it resemble a Buddhist alms bowl, most often such bowls were used in Buddhist monasteries. On the inner walls, a gray-silver layer of oxidized metals appears, which gives a rich color that does not satiate the eye, as well as a thin, extended, distinct pattern. The right bowl has a color that goes from red-brown on the outside to golden in the middle and blue on the inside, which is why the bowl is called "three-colored"

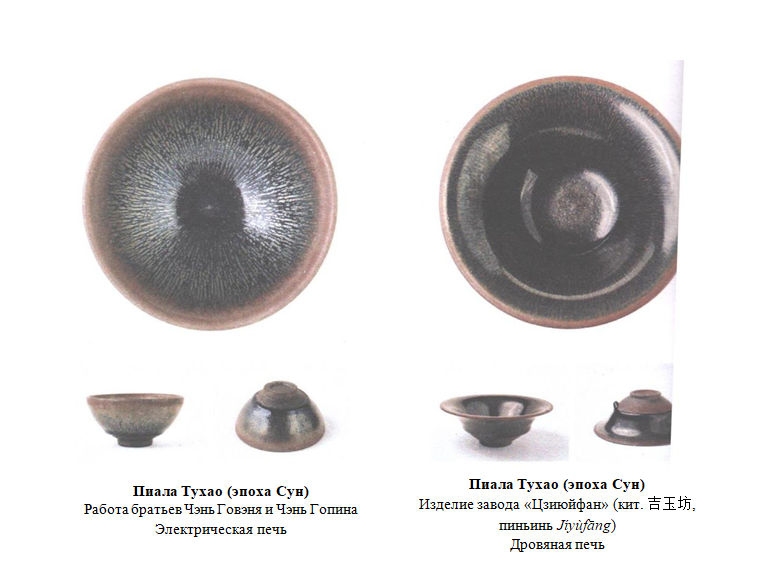

The photo shows two Tuhao bowls, on the left is a bowl fired in a modern electric kiln, and on the right is a bowl fired in a wood kiln. The glaze pattern on the electric kiln bowl is more controllable, the silver "hairs" are long and thin, giving a slight blue glow, but the red tint from oxidation is quite distinct at the edges. As for the wood kiln, one such kiln can produce glazes of different colors in one firing. The use of wood kilns allows for the creation of truly beautiful Tuhao bowls, such as the bowl in the photo on the right; such bowls are extremely rare.

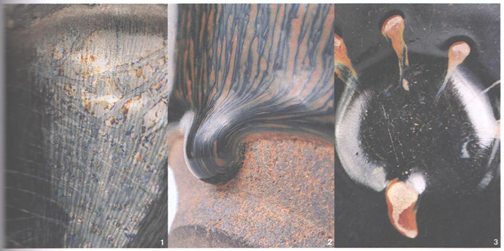

Photo 1. An example of the "pearl-in-shell" effect caused by glaze accumulation. The bowl was found in the ruins of an ancient pottery settlement.

Photo 2. A drop of glaze on a Tuhao bowl.

Photo 3. An effect called "Flying Glaze" (Chinese: 飞釉, pinyin: Fēiyòu). It occurs when the clay used for the blank is too dry or when there are uneven surfaces, which causes the glaze to "pull" into such a pattern during the firing process. It is usually considered a defect, but is nevertheless of interest from an aesthetic point of view.

Photo 4. Crystal pattern on the “Golden Tuhao” bowl.

Photo 5. Crystal pattern on the Silver Tuhao bowl.

Photos 6, 7, 8. Crystal pattern of the Tuhao bowl under a magnifying glass (60x magnification).

In the photo: A fragment of Yudi's bowl (Song era).

Collector: Zhou Jianping (Chinese: 周建平, pinyin: Zhōu Jiànpíng).

Yudi / Zheguban

The word "Yudi" (Chinese: 油滴, pinyin: Yóudī, literally "Oil Drops" ) comes from Japan, which is why many researchers prefer to use the original Chinese name from the Song era - Zheguban (Chinese: 鹧鸪斑, pinyin: Zhègūbān, literally "French Flapper Spots" , i.e. spots like those of a francolin bird) instead; both words refer to the same glaze pattern. However, there is no consensus on the exact definition of the term "Zheguban ": some scholars believe that "French Flapper Spots" is the pattern that we today call "Yudi" or "Oil Drops" ; others believe that only the pattern of a black background and white circles can be considered true Zheguban . In this article we will follow the most common approach among experts to the designation of this type of glaze, and will refer to the mottled pattern resulting from the application of the "duckweed technology" (see below) as "oil drops" (Yudi), rather than as "turach spots".The diameter of large "oil drops" can reach 3-4 mm, while small ones are usually no larger than the tip of a needle, and the drops are golden or silver in color. According to Master Li Da, the mechanism by which "oil drops" are formed on Jianzhan -style bowls can be described as "duckweed technology" (Chinese: 浮萍机理, pinyin: Fúpíng Jīlǐ), as opposed to the "bubble technology" used to create Yudi bowls in another style, the Huabei style (Chinese: 华北, pinyin: Huáběi, literally "Northern Chinese style"). The "duckweed technology" can be simplified as follows: when approaching a temperature of about 1300 °C, iron oxide disintegrates into simple iron and oxygen, and oxygen bubbles continuously fly out of the boiling glaze and gather around the simple iron "floating" in the glaze. This process resembles the duckweed plant, which similarly floats on the surface of water. When 3-5 of these "duckweed leaves" collide, they gather into one large cluster, which creates the Yudi pattern, but under a microscope it can be seen that the individual "duckweed leaves" are close to each other, but do not merge, some distance can be discerned between them.

If the temperature is further increased by about 10 °C, the Yudi pattern disintegrates, the glaze melts again and, flowing down in the form of long "threads" , forms a different pattern - Tuhao . When choosing a Yudi bowl, you should pay attention to the following. In Yudi bowls of the best quality, the "oil drops" should be round or ovoid, should be evenly and densely distributed along the outer and inner walls of the bowl, they should be silvery-white in color, and should also shine. Some bowls may also have a natural effect of rainbow seven-colored shine, called "Shell Pearl Shine" (Chinese: 蛤蜊光, pinyin: Gélí Guāng, literally "Shellfish Shine" ) due to its similarity to the effect of pearl shine in mollusk shells. Modern bowls are also divided into several types: Blue Yudi, Multicolored Yudi and Golden Yudi , and when choosing bowls of these types, it is worth paying attention to the intensity and expressiveness of the corresponding color. Also note that this article does not consider bowls that were fired using chemical glazes.

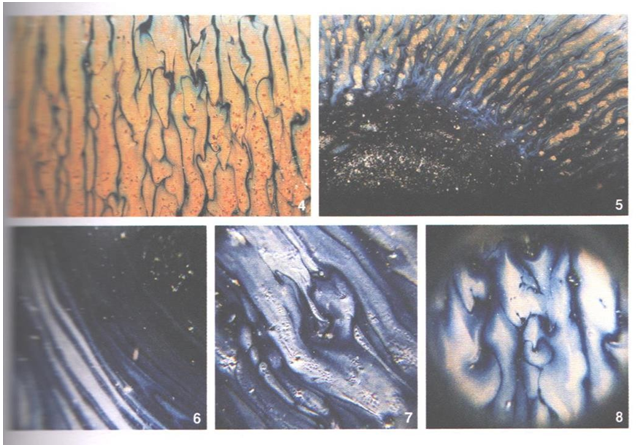

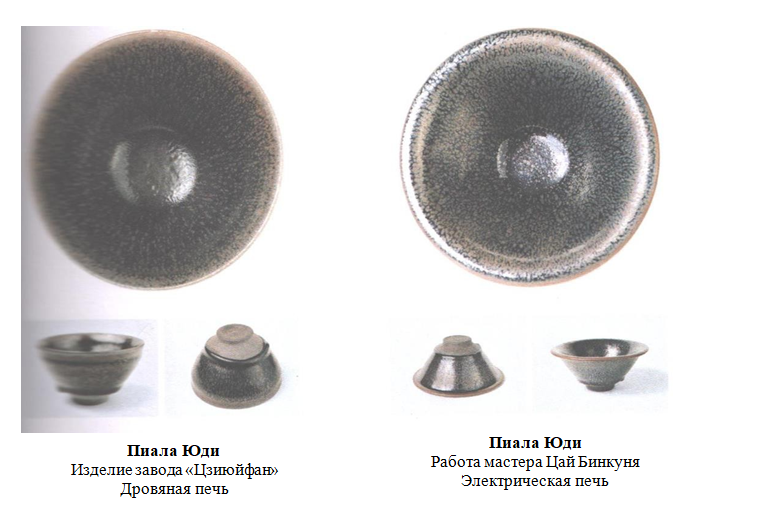

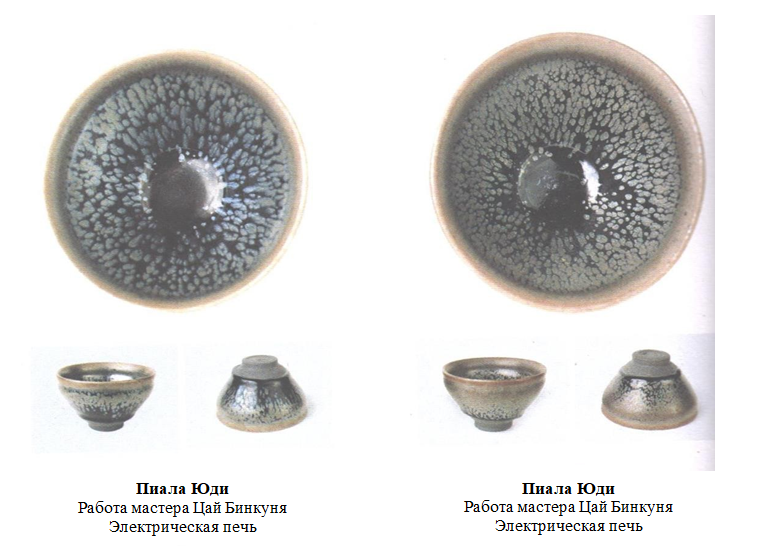

Both bowls shown are excellent examples of the Liankou- style Yudi bowls. The bowl on the left is made of thick clay, with the "oil drops" visible only in places. The right picture shows a modern Yudi bowl, fired in a wood-fired kiln.

On the left is a modern Yudi bowl, fired in a wood-fired oven, the pattern of "oil drops" looks very natural. On the right is a Yudi bowl from an electric oven, the pattern on the glaze of such bowls is easier to control, but such beautiful examples are extremely rare.

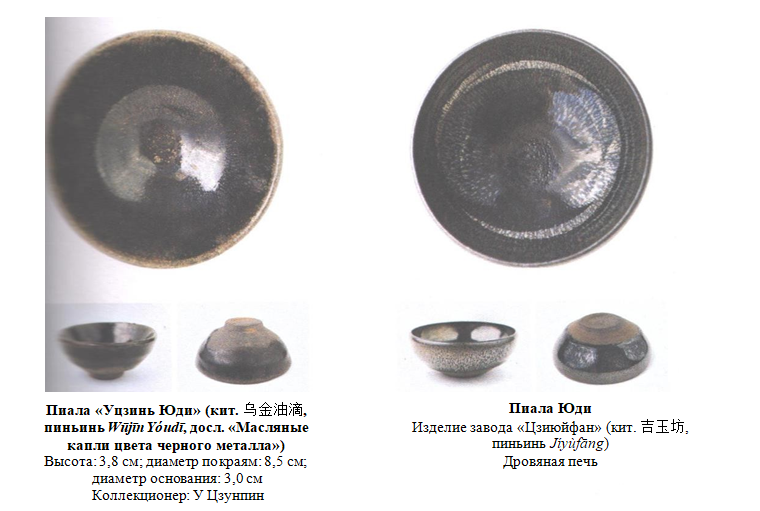

Both of these Yudi bowls were fired in an electric kiln, the left bowl has a glaze color closer to blue, and the pattern of "oil spots" is a little blurry; the right bowl has "oil drops" that are more round and distinct, and under the influence of tea brewed in the bowl, over time it can develop a beautiful effect of rainbow seven-colored radiance.

The left photo shows the "Golden Judi" bowl; the glaze surface of the bowl in the right photo has a rich shine.

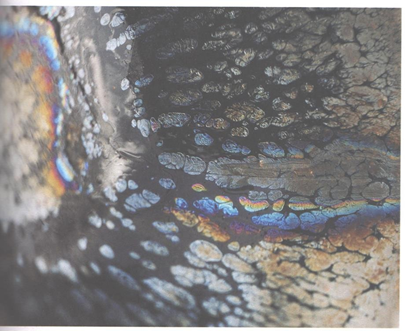

Part of the Yudi bowl. Some of the "oil drops" have a rainbow-colored glow (similar to the glow of the Yaobian bowls).

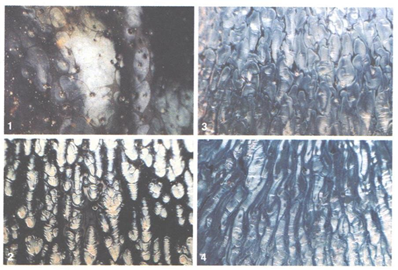

Photo 1. On the dark background of the glaze there are countless small silver spots, giving a metallic sheen.

Photo 2. Crystal pattern on Yudi's bowl from an electric oven.

Photo 3. Crystal pattern on Yudi's bowl from an electric oven.

Photo 4. Crystal pattern on a Yudi bowl from a wood stove.

Part of a Jianzhan bowl with Shihong glaze (Song Dynasty).

- Comments

- Vkontakte