Chinese Celadon Porcelain (Qinqi 青瓷)

The history of Chinese Qing Ci celadon goes back to the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. Created in the 13th-12th centuries BC, it reached its greatest popularity during the reign of the Song emperors. Literally translated, 青瓷 means "greenish porcelain". The jade glaze made it one of the most recognizable and, as the ancient Chinese said, "the best under heaven."

Celadon Porcelain Manufacturing Technology

The molding dough of Chinese glazed porcelain is made from white clay (kaolin) with the addition of the finest mineral powder. Iron oxide is included in the celadon glaze as a coloring component. At a firing temperature of +1300°C, it gives the products greenish shades of varying intensity. And gas bubbles and microscopic quartz crystals that refract light, due to multiple glazing, add a spectacular wet shine.

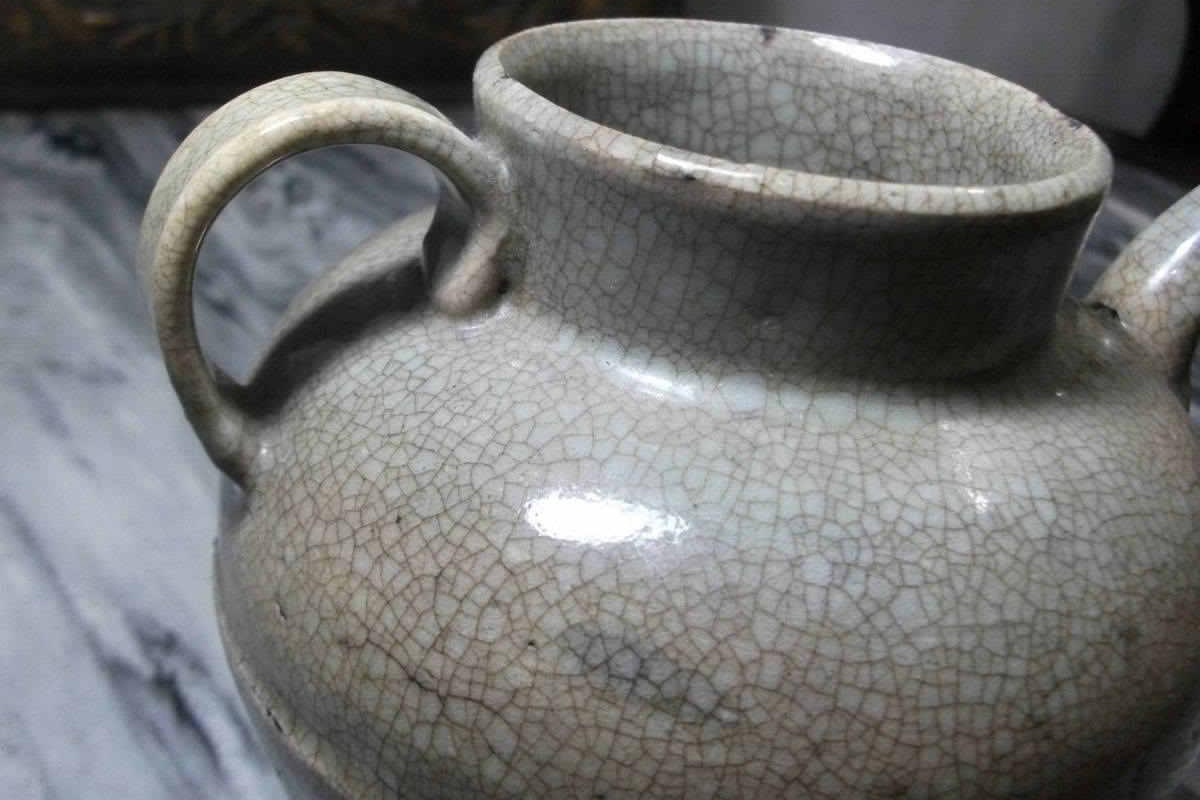

Due to the uneven cooling rate of the base and the glaze covering it, tiny cracks appear on the surface of the dishes, making the porcelain look like semi-precious jade.

Hypotheses about the origin of the name "celadon"

The term "celadon" did not come from China, but was coined in Europe. There are 3 hypotheses of its origin.

According to the first version, the Chinese porcelain Qing Tsi owes its name "celadon" to the hero of the French pastoral novel "Astrea" by Honore d'Urfé. Celadon was the name of the young shepherd, the lover of the main character, who wore light green clothes. At the beginning of the 17th century, when regular deliveries of goods from the Far East began, and Europeans first became acquainted with this type of Chinese porcelain, shepherd's bucolics were the most popular. Since then, this name has stuck.

According to another version, "celadon" is a combination of two Sanskrit (ancient Indian) word forms "sila" and "dhara", meaning "green stone".

There is another hypothesis that celadon porcelain got its name in honor of Salah ad-din Ayyubi (Saladin), the Ayyubid sultan. According to legend, he sent as a gift to the prince of the Nogai Horde, Nur ad-Din, 40 ceramic tea-drinking items covered with a grayish-greenish glaze with a pattern of thin intertwined threads.

Celadon Porcelain Production Centers

The birthplace of Qing Ci is the eastern province of China, Zhejiang. As the porcelain industry developed, other imperial manufactories were formed. Subsequently, the greatest fame and world recognition were gained by 5 centers for the production of celadon porcelain, each with its own unique style:

- Jun Yao (Chinese 钧窑, pinyin jūnyáo) - Junzhou porcelain;

- Zhu Yao (Chinese 汝窑, pinyin rǔyáo) - Zhuzhou porcelain;

- Guan Yao (Chinese: 官窑, pinyin guānyáo);

- Ge Yao (Chinese: 哥窑, pinyin gēyáo);

- Ding Yao (Chinese: 定窑, pinyin dìngyáo) - Dingzhou porcelain.

Jun Yao 钧窑

A characteristic feature of Jun Yao ceramics, which distinguished it from the products of other manufactories, was its massiveness. Porcelain dishes for tea drinking, made in Henan Province, were covered with a very thick layer of iridescent glaze with a never-repeating pattern. This made it thicker-walled and, one might even say, rough. Due to the unimproved, at that time, firing technology, about 70% of the total amount of celadon porcelain was rejected, and the remaining 30% cost an incredible amount of money. By order of the master of the tea ceremony of the 18th emperor of the Song Dynasty, Hui Zong, no more than 36 units of Jun Yao dishes were allowed to be made annually. That is why only a few have survived to this day.

Zhu Yao 汝窑

Zhu Yao tea porcelain , produced in the Henan province, gained its popularity due to its virtually devoid of ornamentation texture and the web of cracks characteristic of celadon. Depending on the direction and density of the cracks, the craquelure mesh acquired the outlines of fish scales, cicada wings or crushed ice. At first, the effect of production cracks was perceived as a defect arising from an excessively thick layer of glaze and very rapid cooling. However, later, most of the Chinese nobility sought to become the owners of Zhu Yao porcelain. The reason for this is its rapid visual "aging". From tea drinking to tea drinking, the drink penetrated into numerous cracks and colored them brown, giving the dishes a special patina of antiquity.

Many centuries ago, the technology of making Qing Qi Zhu Yao, popularly called elder brother ceramics, was lost, and only in the 20th century it was restored again and continues to improve.

Guan Yao 官窑

Thin-walled Guan Yao ceramics (literally translated as "state ceramics") were intended only for Chinese emperors and their entourage. A distinctive feature of this porcelain was a rusty rim that formed along the very edge of the vessel. This phenomenon, which occurs due to the release of iron oxide included in the glaze, received the poetic name "brown mouth" or "iron foot".

Ge Yao 哥窑

Ge Yao's celadon porcelain, which has almost disappeared, is the oldest type of pottery from the Five Dynasties period. Fired in the "old kilns" of Zhejiang, it has its own characteristic features: a crackle effect, darker shades of sea green, and translucent stripes on the edges.

Ding Yao 定窑

Ding Yao porcelain, produced in Hebei Province (Dingjia region in ancient times), was considered one of the most valuable and was made only for imperial tea ceremonies. The highlight of this tableware, which attracted the attention of influential nobles, was the engraving and thin gold or silver rim. In this way, Chinese craftsmen eliminated a purely technical problem - the impossibility of covering the edges of cups and bowls with glaze as completely as possible.

As time goes by, ceramic production technology is constantly improving. However, Chinese celadon porcelain exists in a timeless framework, consistently demonstrating the highest level of pottery craftsmanship.