Sbiten, vzvara, Ivan tea and other drinks from the pre-tea era

If you ask any Russian today: "What is the main non-alcoholic national drink?", then in the overwhelming majority of cases we will hear about tea. In the category of non-alcoholic drinks, tea is beyond competition. But tea came to the European part of Russia only in the 17th century. What drinks did Russians drink before the arrival of tea and in parallel with it? We will try to answer this question.

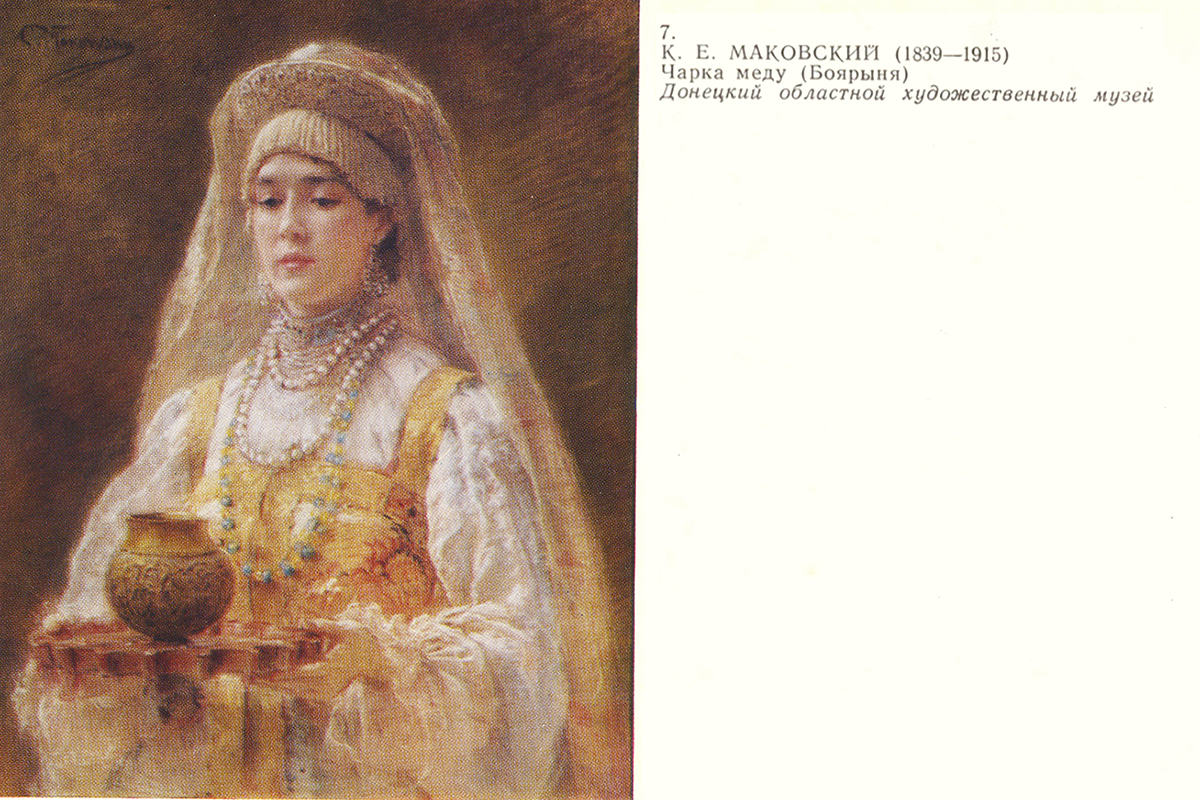

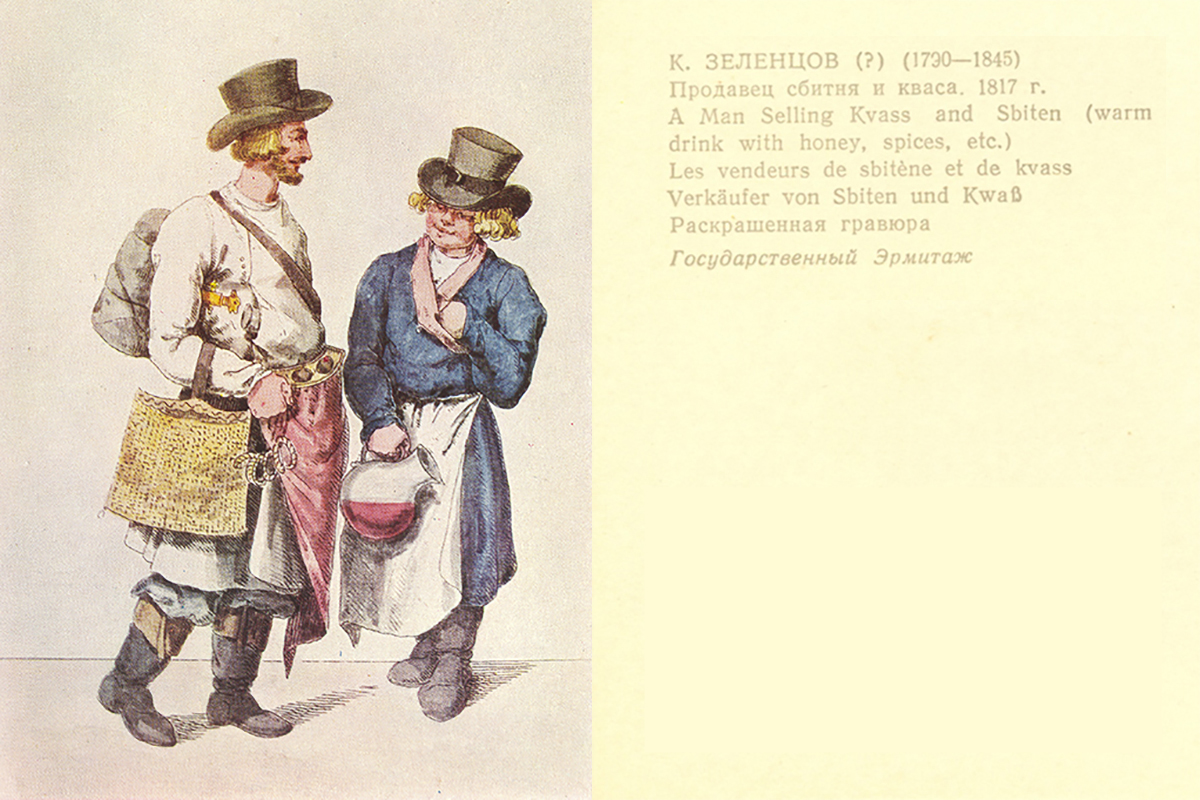

Sbiten and kvass. "Divyi med".

One of the most curious hot non-alcoholic drinks was sbiten, which was made from honey and a variety of herbs and spices. There was no single recipe for sbiten - each sbiten maker had his own secrets regarding the composition of the drink, the percentage of components, brewing methods, etc.

At the end of the 19th century, a curious honey-based drink appeared in the Russian Empire. At fairs, you could often meet people selling “divy myod” (another name for the same product is “wild honey”). Large pieces in the form of sausages or cylinders were made according to various recipes.

The product recipes were based on honey and a set of different components (herbs and dried fruits), which varied depending on the manufacturer. The consumer would grind up pieces of this "sausage" and brew them. According to those who tried the product, the infusion had a sweetish-cloying taste. But the undemanding buyer liked this domestic product.

Among cold non-alcoholic and low-alcohol drinks, kvass was extremely widespread. In the 19th century, there were countless recipes for various kvass. It is safe to say that there were several thousand different unique recipes, most of which are now lost.

The nobles who loved kvass in the first half of the 19th century made and served it at the table, sometimes ten types at a time. Kvass was often made on fruit and berry bases. There were raspberry, apple, strawberry, cherry, pear, honey and other, very diverse, kvass. The history of making kvass and its recipes deserve a separate discussion.

Brews/brews.

In the "pre-tea" era, various peoples of Russia had a lot of traditional drinks made from plant materials, which were called vzvary or vzvartsy. Today, the same drinks are usually called tisanes in the French style (tisane - decoction).

These drinks and their proportions in consumption varied significantly depending on the region. People empirically identified useful plants in the world around them and prepared drinks from them. Often, the raw materials for drinks were collected in forests and fields in large quantities and dried for the winter.

Orthodox monasteries played a major role in the spread of decoctions. Monks prepared various medicinal plants and berries (they varied depending on the area), often dried them, and then made drinks that allowed them to hold long services and endure fasts.

Since at least the 1830s, the Russian language also had the term "herbal tea." It was used to describe a drink made from brewed leaves and berries of various plants.

Often, "herbal tea" was used as a stand-alone medicine, or as a supplement to medicines, as indicated by the semantic context of a number of sources, starting from the 1830s.

"Koporsky tea" and fireweed (Ivan-tea, epilobium).

The most common drink in Russia in the 19th century was made from fireweed. It was consumed en masse by those who could not afford Chinese tea. In addition, due to its prevalence, it was a very convenient raw material for the production of counterfeit.

The drink fireweed has been prepared since ancient times. There are many beautiful legends about who was the first to start mass production of fireweed and put the technology "on stream". None of the legends have yet been supported by serious archival material.

"Tea" made from dried fruits.

Since the end of the 19th century, a number of regions of the Russian Empire began to produce tea from dried fruits. The recipes varied significantly. In some cases, dried fruit peel and crushed seeds were added to dried pieces of fruit. Chicory was often added to such a dried mixture. In trade, such a drink was often called "fruit tea".

When the composition for the future fruit drink included only dried fruit pulp (apples, pears, etc.), then it cost the consumer 50-60 kopecks per 1 pound.

If a large amount of low-grade raw materials were used for the production of fruit tea - peel, ground seeds, etc., then chicory was often added, which softened the product's shortcomings. At the same time, the product was already significantly cheaper on sale - 30 - 40 kopecks per 1 pound.

Often, such tea was packaged in bags, sacks and packs. Packaged "fruit tea" cost 3, 5, 10, 20, 25, 50 kopecks on sale.

Small producers bought the collected fruits from the peasants, chopped them up (cut them with knives, and often simply chopped them with hoes), and dried them in ovens. The production costs were minimal.

The demand for "fruit tea" was quite stable, as it was cheap to produce. This tea substitute was most widely distributed in the Oryol province, from where it was actively distributed to other regions.

In the last years of the 19th century, the Samara province also joined the production of “fruit tea”.

Even the merchant capital of Russia, Moscow, quickly appreciated the prospects of commercial production of the new product; “fruit tea” began to be produced here as well.

The development of competition led to the emergence of a large number of different “blends”: in addition to chicory, wine berries (as figs were called in the 19th century), dried prunes, dried pumpkin and its seeds were often added to the mixture.

Since the 19th century, "carrot tea" has been actively produced in Russia, which was actively consumed, including by the Old Believers. During the First World War and the Civil War, most Russians became closely acquainted with "carrot tea".

Unlike Chinese tea, such drinks had a pleasant sweetish taste when prepared. A big disadvantage of a number of "fruit teas" was that they could only be drunk hot, since the cooled drink often became tasteless and had an unpleasant appearance.

Since 1888, the Russian Empire has banned the use of the word "tea" to refer to fruit drinks. The ban only concerned terminology. Tea substitutes themselves could still be made and sold.

It should be noted that the mass distribution of tea substitutes began during the First World War, the Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent Civil War. The blocking of the main tea supply routes, the impoverishment of the population, and then devastation led to the mass distribution of tea substitutes among the people.

The Soviet government not only took up the development of domestic tea plantations in the Caucasus, but also organized the mass production of tea substitutes. Tea drinks were actively advertised even in the 1950s. The taste of tea drinks "strawberry", "aroma", "berry", "raspberry", "wild strawberry", "pear" was well known to consumers.

Tastes of different peoples of the Russian Empire.

Russian travelers, traders and explorers, while exploring new lands, paid attention to the life and traditions of the indigenous peoples. Quite a few different memoirs remain, which tell about traditional drinks in different regions of the Russian Empire.

On the Amur, there was a tradition of drinking tea containing admixtures of local herbs. One of the Russian travelers recalled how he drank such tea with herbs: "The hosts themselves (ordinary Cossacks, not officers) prepared tea with various Siberian potions, unsightly, but very tasty."

In a number of regions of Siberia, in Transbaikalia, in Altai, bergenia (Bergenia), also known there as "Chagyrsky" tea, was actively consumed. Many Russian settlers in Siberia actively harvested, sold and consumed bergenia.

For a long time, bergenia was no less an important commodity than tea and, according to the Englishman Samuel Collins, was delivered to Russia from China: “From there [from China via Siberia] he [an unnamed merchant, Collins’s acquaintance] brought tea (Chay) and Badian (Bour Dian). Badian is called Anisum Indienun Stellatum. Merchants say that it is used with sugar (as we do in England) and is considered very useful for lung disease (flatus Hypochondriaci) and stomach upset. It is brought wrapped in pounds in paper with Chinese letters written on it.”

Old Believers who did not take the "infidel potion" - Chinese tea, ours in Siberia have many different substitutes for it. Quite actively drinks were made from plants of the Oxalidaceae family. In particular, the herb skripun (hare cabbage) was used to make drinks.

The Old Believers also drank Kuril tea (cinquefoil, Turusulnik), brewed currant and lingonberry leaves (lingonberry). The Old Believers also prepared drinks from chaga (birch mushroom, Inonotus obliquus) and shulta (rotten birch heartwood).

It should be noted that not all Old Believers did not accept Chinese tea. Unlike coffee, many Old Believers did not see any evil in the "khan's herb" - tea. Moreover, there were many Old Believers tea merchants who both drank tea themselves and sold it.

To be sure, I can give an example from the end of the 18th – beginning of the 19th century – Tolstikov Yakov Filippovich. An Old Believer from Yekaterinburg, a major industrialist and merchant. He sold tea. From 1805 to 1811, he was even the mayor of Yekaterinburg. There are many such examples.

For a long time, rhubarb was actively consumed by many peoples of Russia. It was collected both in the territories of Russia itself and purchased in huge quantities in China. Moreover, rhubarb root, purchased in bulk from the Chinese, was re-exported to a number of European countries.

The so-called "ulaazhargyn sai" ("ulaazhargyr sai") was popular among the Buryats. Its technology was simple: withered and curled fireweed leaves were collected and placed in a suitable vessel. They were moistened with fresh brew of the same ulaazhargyn sai and placed in a warm place for fermentation, then brewed with the addition of milk. In Buryatia, ulaazhargyn sai is popular even today.

Since the technologies for making Ulaazhargyn Say and Koporye tea are similar, this gives grounds for another assumption. This may (albeit indirectly) indicate that both expensive Chinese tea and a cheap, very accessible method of counterfeiting it were brought in along the Great Tea Road through Buryatia.

The inhabitants of the Kuril Islands in the 17th to 19th centuries consumed a drink "made from yellowish leaves; they consider it a cure for colic."

In the Russian Volga region in the 19th century, people actively drank a drink made from thyme (also known as creeping thyme, thymus serpyllum). Often, licorice (glycyrrhiza echinata) was added to the thyme drink.

Beverages made from various plant materials were actively consumed in the 18th and 19th centuries by the Bashkirs and Russian settlers in the Urals.

Since the 18th century, residents of the Yaroslavl province have been quite actively harvesting wild strawberry leaves (Fragária vésca). "Strawberry tea", as it was popularly called, was quite actively served even at the Nizhny Novgorod fair as a cheap replacement for expensive Chinese tea.

In the 19th century, poor residents of Central Asia and Turkestan quite actively consumed a drink made from several species of the oregano plant. One of the Russian merchants in the city of Verny (modern Alma-Ata) in the 19th century petitioned the authorities for the privilege of making “Russian tea” based on oregano.

A significant amount of origanum vulgare and herbal mixtures based on it were imported to Russia from China from the end of the 19th century. The product was cheaper than Chinese teas and demand for it on the market generated supply. Often, such a mixture was pressed into large tiles, briquettes and shapeless pieces and in this form it was delivered from China to a number of regions of Central Asia, which by that time had been annexed to Russia.

The drink was made from the leaves of the Caucasian lingonberry. It was often used to adulterate tea. This adulteration was known in the Caucasus under the names "Caucasian tea" and "Batumi tea". It was often mixed with tea produced by Russian tea plantations in the Caucasus.

Linden blossom, apple and oak leaves, St. John's wort, sage, chamomile and other herbs were also used to prepare drinks.

Author: Candidate of Historical Sciences Ivan Alekseevich Sokolov

- Комментарии

- Вконтакте